Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, commonly known as CPR, is a vital life-saving technique employed when someone’s heart unexpectedly ceases to function. In emergencies requiring CPR, the first few minutes can be the determining factor between life and death. CPR maintains blood circulation and oxygen supply to the brain and essential organs until professional medical help arrives. This urgent necessity highlights the difference between receiving immediate assistance and the tragic outcome when intervention does not occur.

However, emerging research indicates that CPR application is not uniform across gender lines. A comprehensive Australian study analyzed nearly 4,500 cases of cardiac arrest between 2017 and 2019, revealing an unsettling trend: bystanders were significantly more likely to provide CPR to males (74%) compared to females (65%). This discrepancy raises pressing questions about the underlying factors that contribute to such bias in life-saving interventions, particularly when seconds count against the clock.

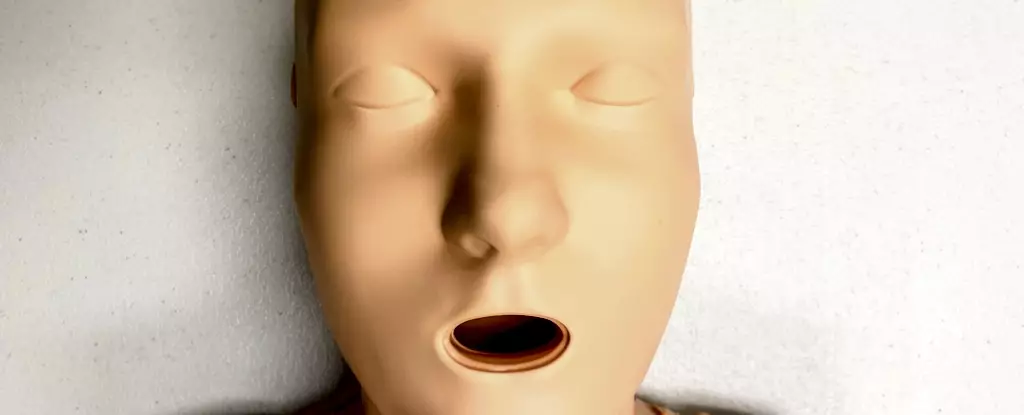

A remarkable observation from the study concerns the training manikins used in CPR instruction. Most of these manikins, which are essential for teaching CPR technique, lack anatomical features associated with female bodies, particularly breasts. Research indicates that 95% of CPR training manikins have a flat-chested design. While anatomically, the presence of breasts does not alter the CPR technique per se, it may deter bystander action, conjuring discomfort and hesitation in critical moments.

The lack of representation in training tools can foster an implicit bias among potential rescuers. This means that when bystanders are faced with a real-life medical crisis involving a woman, they might be less inclined to provide assistance due to unfamiliarity or discomfort built from their training experience. Thus, ensuring a diverse range of CPR manikins that include realistic representations of all body types, particularly those of women, is pivotal in closing this gap.

Statistics reveal troubling realities about cardiovascular diseases among women. Conditions such as heart disease and strokes manifest in women and frequently lead to life-altering consequences, including increased mortality rates. Astonishingly, women experiencing cardiac arrests outside hospital environments are 10% less likely to receive CPR compared to their male counterparts. Moreover, even among those who do receive CPR, women have poorer survival rates and a higher likelihood of sustained brain damage post-arrest.

This gender disparity extends beyond immediate rescue efforts, touching on broader healthcare inequities faced by women and marginalized groups such as transgender and non-binary individuals. Symptoms exhibited by these populations are often overlooked, misdiagnosed, or trivialized, leading to delays in critical medical intervention.

Barriers to Performing CPR on Women

The successful performance of CPR hinges not merely on the mechanics of the technique but also on the willingness of bystanders to engage. Numerous factors deter potential helpers, particularly when the victim is a woman. Fear of being accused of inappropriate behavior, apprehensions about causing harm, or reluctance around touching a woman’s body are significant barriers. Research suggests that even in simulated emergency scenarios, bystanders showed reluctance to expose a woman’s chest in preparation for resuscitation.

Such findings underscore a critical need for public education that emphasizes both the urgency of performing CPR regardless of gender and the techniques necessary to do so effectively. The discomfort linked with having to remove clothing in the event of a defibrillator application, including underwires from bras, should not deter intervention.

Revamping CPR Training for Inclusivity

To bridge the gender gap in CPR performance, a shift in training practices is essential. Current CPR courses predominantly feature flat-chested manikins, reflecting a male default. This not only perpetuates the bias against female patients but also diminishes the presentation of inclusive training. A recent study noted that the majority of CPR manikins were not representative of the diversity in skin tone and body size, with only 5% being indicated as “female” and even fewer including realistic anatomical features.

To truly prepare bystanders for real-life emergencies, training programs must evolve to incorporate a wider array of CPR training manikins that reflect the diverse body types and identities of the populations they serve.

Raising awareness about the signs of cardiac arrest is crucial for increasing the number of successful CPR interventions. Potential victims may be unresponsive or exhibit irregular breathing patterns, and in such cases, immediate action can make a difference. Training should emphasize that the technique is the same regardless of whether the recipient has breasts – starting CPR promptly and effectively can save lives.

Addressing the gender disparities in CPR interventions necessitates an intentional effort to broaden representation in training materials while enhancing public awareness about women’s unique health risks. Expanding the diversity of CPR training manikins along with educational campaigns can empower bystanders to take action without hesitation, ultimately contributing to fairer health outcomes and saving lives.