Anorexia nervosa, a complex and debilitating eating disorder, poses substantial risks to patients’ mental and physical well-being. Characterized by self-imposed starvation, an intense fear of gaining weight, and distorted body image perceptions, anorexia affects not only those who struggle with it but also those around them. Recent research sheds light on the potential neurological influences behind this condition, particularly concerning neurotransmitter functions in the brain. This article will explore these findings and their implications for future treatments of anorexia.

Anorexia nervosa is often marked by a relentless pursuit of weight loss and an obsessive focus on food, body shape, and weight. Beyond the visible signs of malnutrition, patients frequently experience comorbid disorders such as anxiety and depression. These issues complicate the treatment process, making it crucial to understand the multifaceted nature of anorexia. Recent studies suggest that a deeper investigation into the neurological underpinnings of this disorder could lead to more effective management techniques.

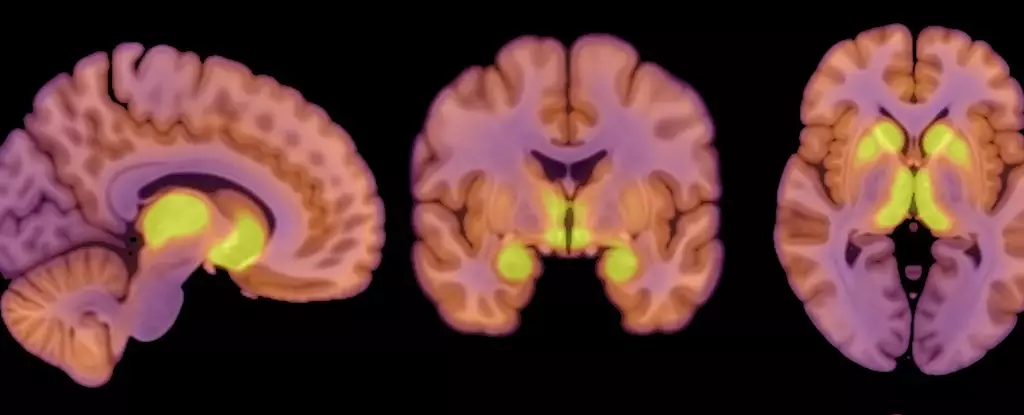

A groundbreaking study involving patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa has brought to light how changes in neurotransmitter function, particularly regarding the mu-opioid receptor (MOR) system, play a role in this disorder. The research focused on the opioid neuropeptide system, which normally governs processes related to appetite and pleasure. By analyzing both anorexia patients and healthy controls, researchers could compare the availability of MORs and brain glucose uptake, important factors in understanding energy regulation in the brain.

The cohort of study participants included 13 women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and 13 healthy controls, allowing for a balanced examination of MORs in different populations. The PET scans revealed that patients faced increased MOR availability linked to reward processing in the brain. This elevation can contribute to altered eating behaviors, as the brain prioritizes certain functions even when the body is in a state of starvation.

Interestingly enough, notwithstanding the reduced caloric intake associated with anorexia, the study indicated that the brains of these patients utilized glucose similarly to those of healthy individuals. This revelation is significant: it shows the brain’s remarkable ability to adapt by prioritizing its energy needs, a self-preservation mechanism that can be detrimental in the long run. The findings suggest that the brain can operate at a status quo even when the body faces an energy deficit, indicating that neurological pathways may be fundamentally altered in anorexia patients.

The study’s results pose profound questions about the connection between the MOR system and anorexia nervosa. Clinically significant elevations in MORs, as identified in the study, may represent a critical piece of the puzzle regarding the control of eating behavior in anorexia and perhaps other eating disorders. While previous studies have highlighted the down-regulation of this system in obesity, the researchers propose a “mirror image” phenomenon in which anorexia displays dysfunctional opioid neurotransmission that elevates appetite inhibition instead of promoting eating behavior.

However, this raises additional inquiries: Is the altered MOR function a causal factor leading to anorexia, or does it stem from the disorder? The directionality of the relationship between altered neurotransmitter function and eating behaviors necessitates further exploration, signaling an urgent need for more extensive research involving larger and diverse samples.

Although the current study provides essential insights, it cannot be seen as a definitive conclusion regarding anorexia’s origins and treatments. The limitations underscore the necessity for a more inclusive narrative in future research. Findings based entirely on a female cohort restrict the generalizability of these results. Moreover, the small sample size necessitates cautious interpretation.

To advance our understanding of anorexia nervosa, more rigorous investigations are required that encompass both male and female patients and a wide range of neuropathological variables. The relationship between dopamine dysregulation and eating behaviors, as well as the psychological components, must also be taken into account when considering treatment pathways.

The exploration of neurological components in anorexia nervosa is crucial for developing holistic treatment strategies. Understanding how neurotransmitter functions, specifically within the opioid system, affect appetite and behavior could lead to more sophisticated treatment methodologies. Though much remains to be learned, the interconnected nature of brain functions and mental health offers valuable hope for those grappling with anorexia nervosa. By recognizing and addressing these complex neurological factors, the overarching goal continues to be the restoration of patients to a healthy, fulfilling life.